Architecture Design

What This Is About

Architecture is how you organize your code so you can actually find things six months from now. It’s the difference between “I need to add a feature” taking two hours versus two weeks. Good architecture doesn’t mean over-engineering everything - it means making decisions that keep future changes manageable.

The hard part isn’t choosing between patterns. The hard part is knowing when the simple thing is good enough and when you need something more structured. This guide focuses on the one decision that affects everything else: how to organize your application at the highest level.

You don’t need to understand microservices, event-driven architecture, or hexagonal ports-and-adapters to ship working software. You need to understand the basics and avoid common mistakes that create maintenance nightmares.

The Two Architectures Everyone Talks About

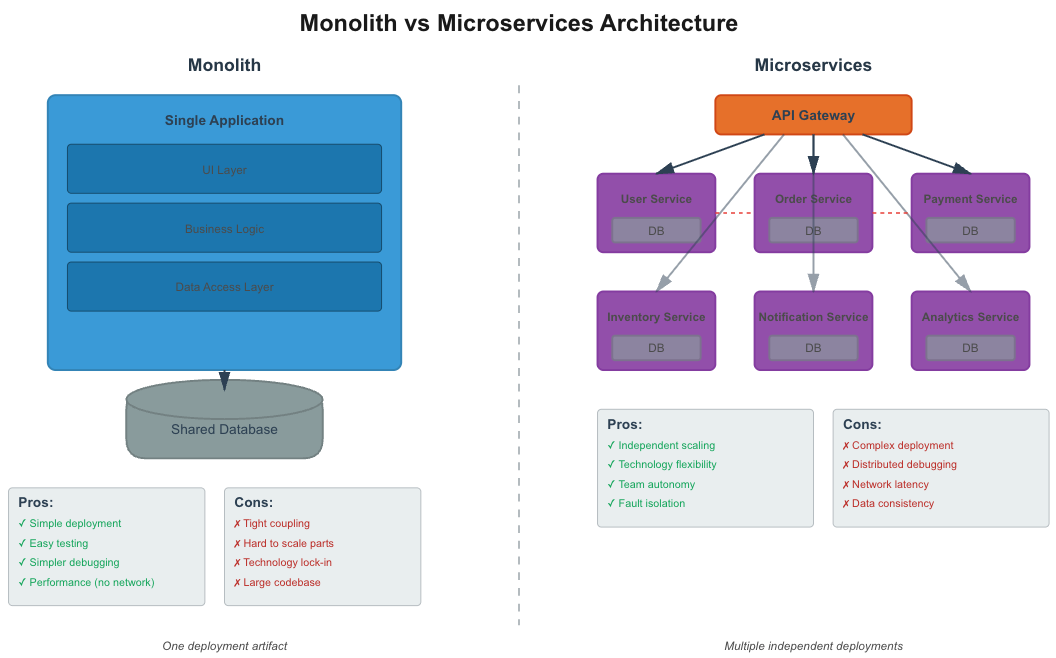

There are dozens of architecture patterns, but two dominate every conversation: monoliths and microservices.

A monolith is one application that does everything. Your code, your database, your background jobs - they all live together in one deployable unit. You change one file, you redeploy the whole thing. Twitter started as a Ruby on Rails monolith. Shopify runs one of the largest Rails monoliths in existence and processes billions in transactions.

Microservices split functionality into separate applications that communicate over a network. Your user service is separate from your payment service, which is separate from your notification service. Each can be deployed independently. Netflix runs hundreds of microservices. So does Amazon.

Figure 1: Monolith vs Microservices - understanding the fundamental architectural difference

The architecture debate usually sounds like this: “Monoliths don’t scale! Microservices are too complex!” Both statements are sometimes true and often wrong.

Here’s what actually matters: monoliths are easier to build and reason about, but can become tangled if you’re not careful. Microservices can scale teams and systems independently, but add operational complexity that will absolutely sink you if you’re not ready for it.

Start With a Monolith (Probably)

Martin Fowler, who has forgotten more about software architecture than most of us will ever know, advocates for “monolith-first” development. His reasoning is simple: you don’t know where the boundaries should be yet.

When you’re building something new, you’re making educated guesses about what belongs together and what should be separate. Those guesses are often wrong. In a monolith, moving code between modules is annoying but manageable. In microservices, you’re moving code between separate applications, rewriting network calls, handling distributed transactions, and probably breaking things in production.

A monolith lets you learn where the real boundaries are. After six months, you’ll discover that the “user profile” and “user preferences” you split into separate services actually need to be together. Or that the “payment processing” you lumped in with everything else really should be isolated.

Start with a monolith. Learn from it. Split it later if you need to.

When to start with microservices anyway: You have a team experienced in distributed systems. You know exactly what you’re building because you’ve built it before. You have strong operational capabilities for monitoring, deployment, and debugging across services. If you don’t check all three boxes, stick with a monolith.

Real-World Example: The Monolith-First Strategy

A dispatch management system for equipment and drivers started as a modular monolith and scaled to 1,000 concurrent users before extracting any microservices. The results were striking:

Cost Comparison:

- Single-server monolith: $50-300/month

- Equivalent microservices architecture: $500-1,000/month

- Savings enabled hiring a second engineer sooner

Development Speed:

- 3x faster development compared to microservices

- No network latency between modules

- Debugging in one codebase instead of tracking requests across services

- Single deployment simplified testing

The Key Decision: They deliberately used an in-memory queue at launch, knowing it would be lost on restart. This wasn’t a failure to fix later - it was an intentional trade-off. Queue losses were annoying but not catastrophic at 10-100 users, and avoiding Redis saved $50/month plus operational complexity. When deployments became daily and queue losses exceeded 2 per month, they migrated to Redis.

When They Finally Split: At 10,000+ users, they extracted only 3 services:

- Auth Service (high request volume - every API call validates tokens)

- Notification Service (CPU-intensive, failure-tolerant)

- Reporting Service (heavy S3 interactions)

What Stayed Together: Users, Equipment, and Dispatch modules remained in the monolith because they needed ACID transactions across all three. Trying to coordinate dispatch operations across separate services would have added distributed transaction complexity for no benefit.

The lesson: Monolith-first isn’t a compromise. It’s the optimal strategy for finding product-market fit. Complexity should be added based on real pain points, not theoretical concerns.

📌 See Full Case Study: Dispatch Management - Progressive Architecture

Finding Components (Even in a Monolith)

A monolith doesn’t mean throwing all your code in one folder. Even in a single application, you need to organize code into logical components. The question is: what makes a good component?

Look for functional boundaries - parts of your system that solve different problems. In an e-commerce app, you have components for products, shopping carts, checkout, and order fulfillment. Each handles a distinct job.

Look for different rates of change. If your pricing logic changes weekly but your user authentication hasn’t been touched in two years, those probably belong in different components. Things that change together should live together.

Look for different scalability needs. Your product catalog might be read-heavy and mostly static. Your checkout process is write-heavy and needs strong consistency. Your recommendation engine needs serious CPU. These are hints about boundaries, even if everything stays in one application.

Here’s a simple exercise: list the nouns in your domain. In a healthcare app, you might have patients, appointments, medical records, billing, and insurance claims. Each is probably a component. Now list the main actions: schedule appointment, update record, submit claim. If an action only touches one noun, that’s a sign of good boundaries. If every action touches every noun, your boundaries might be wrong.

A simple directory structure for an e-commerce monolith:

src/

components/

catalog/

products.py

categories.py

search.py

cart/

cart_management.py

cart_items.py

checkout/

payment.py

shipping.py

orders/

order_processing.py

fulfillment.py

shared/

database.py

auth.py

email.pyEach component has its own folder. Shared utilities live in shared/. The rule: components can use shared utilities, but they shouldn’t directly import from other components. If cart needs product information, it goes through a defined interface, not by directly importing catalog.products.

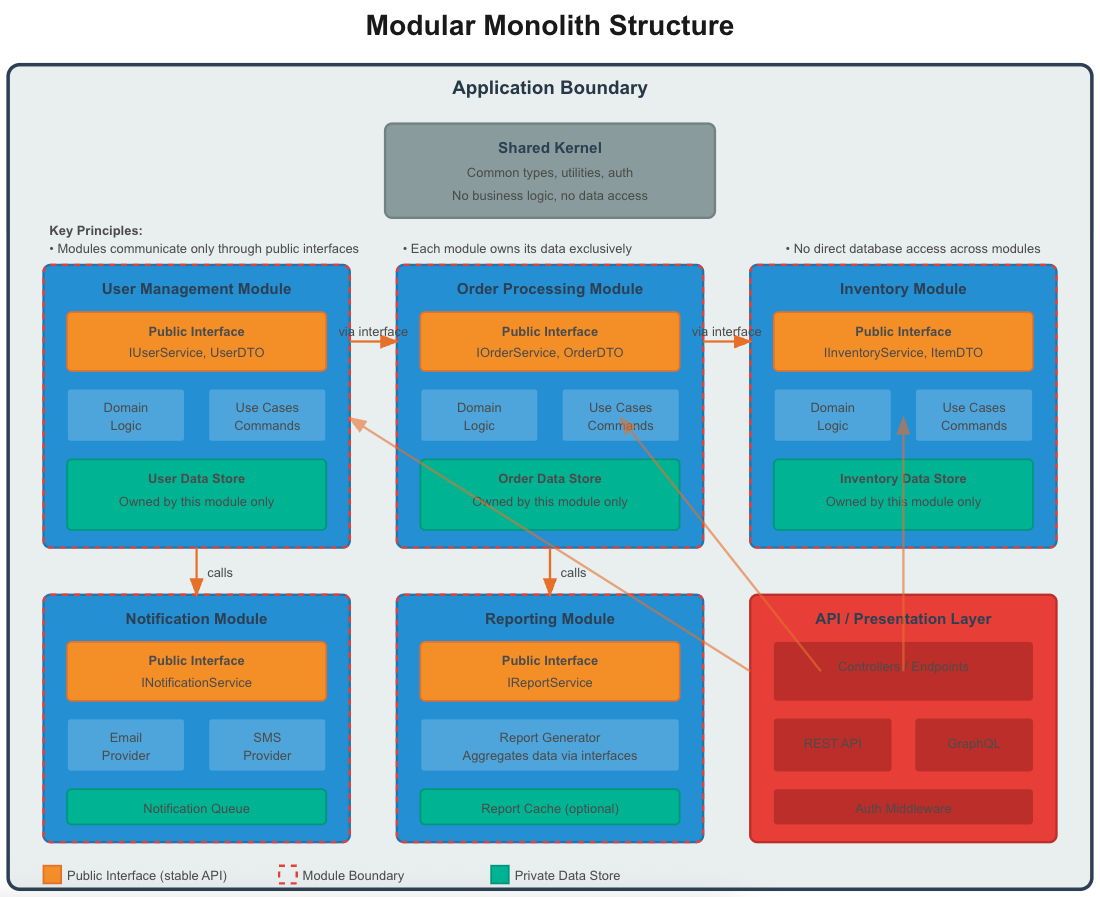

Figure 2: Modular monolith structure with clear component boundaries and shared utilities

The Modular Monolith

A modular monolith is the sweet spot for most applications. It’s one deployable application with strong internal boundaries. You get the simplicity of a monolith with the organizational benefits of separated concerns.

The key is enforcing boundaries even though everything runs in the same process. This usually means:

Clear interfaces between components. Other parts of the system interact with your component through defined functions or classes, not by reaching into its internals.

Separate data ownership. The catalog component owns the products table. The orders component owns the orders table. Nobody writes directly to another component’s tables.

Minimal coupling. Components should interact through simple data structures or events, not by sharing complex objects with lots of dependencies.

Django encourages this with apps. Rails encourages this with engines. Even if your framework doesn’t have explicit support, you can enforce it with code review and folder structure.

A real example: Shopify’s modular monolith has components (they call them “domains”) for products, orders, customers, and inventory. Each component exposes a Ruby API. Other components use that API, never directly accessing another component’s database tables. When they eventually need to extract a component into a microservice, the boundaries are already clear.

The benefits show up in two ways. First, you can understand and work on one component without understanding the whole system. A developer can make changes to the checkout component without accidentally breaking product search. Second, if you do need to split into microservices later, the hard work of defining boundaries is already done.

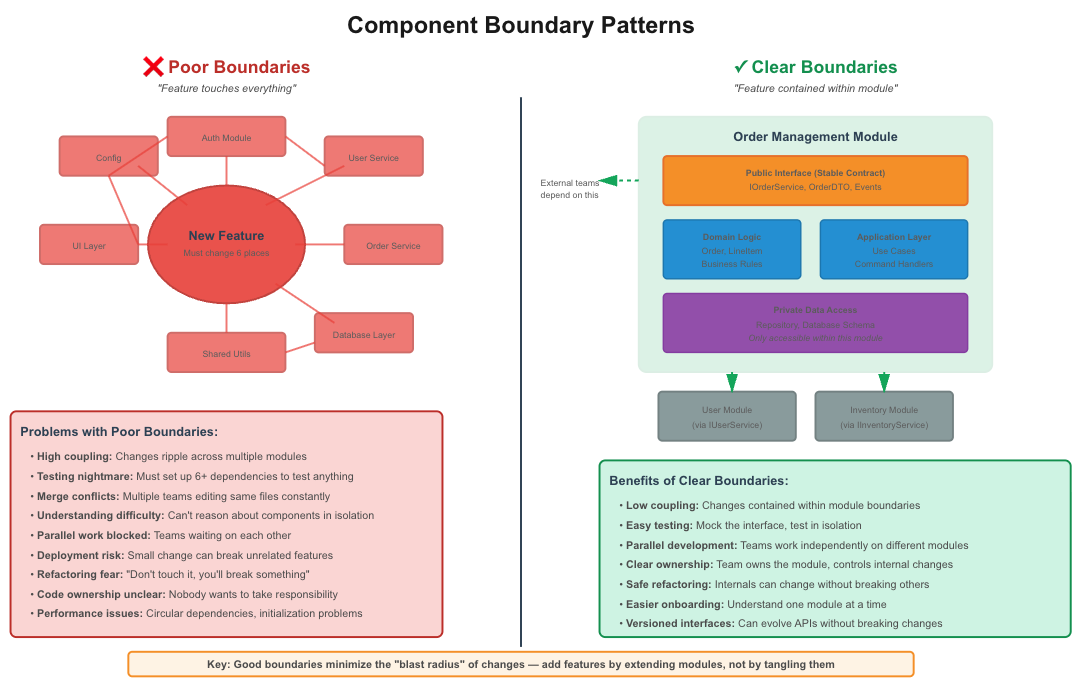

Three Warning Signs You Chose Wrong

How do you know if your architecture is causing problems? These three signs show up reliably.

Sign 1: Every feature touches everything. You want to add a discount code field to checkout. Somehow you’re modifying files in the product catalog, the cart, the order history, and the email system. This means your boundaries are wrong - concepts that should be separated are tangled together.

This happens in both monoliths and microservices. In a monolith, you have too much coupling between components. In microservices, you have services that are sliced wrong, forcing every change to coordinate across multiple services.

Figure 3: Good boundaries (isolated components) vs bad boundaries (tangled dependencies)

Sign 2: You can’t reason about one part in isolation. You’re trying to understand how shopping cart works, but you can’t trace the logic without jumping into checkout, inventory, pricing, and user profiles. The component boundaries aren’t matching the mental model of what the system does.

Good architecture matches how people think about the problem. If explaining how something works requires drawing arrows between fifteen different boxes, something’s wrong.

Sign 3: Deployment is terrifying. In a monolith, you’re afraid to deploy because changing anything might break everything. In microservices, you’re afraid to deploy because changing one service requires coordinating changes across five other services, and if you get the order wrong, everything breaks.

Both situations indicate coupling that your architecture should have prevented. In a well-designed system, you should be able to change and deploy most components independently.

Your First Architecture Decision

For your first version, build a modular monolith. One application, one deployment, one database - but organized into clear components with defined boundaries.

This gives you room to learn. You’ll discover which parts of your domain naturally belong together and which need separation. You’ll see which components change frequently and which are stable. You’ll understand which parts have different scalability or reliability requirements.

After you have real usage, real data, and real pain points, you’ll know if you need microservices. Most applications never do. They scale perfectly fine as monoliths with good component boundaries and maybe some extracted services for specific high-scale needs.

The architecture decision that matters most isn’t monolith versus microservices. It’s whether you create clear boundaries or let everything tangle together. You can have a well-architected monolith or a poorly-architected microservices system. The boundaries matter more than the deployment model.

Next Steps

Before you write architectural code, understand what you’re building and why (see the Job-to-be-Done topic in Discovery & Planning). After you’ve decided on your high-level architecture, you’ll need to design the APIs between components (see API Design) and determine how to structure your data (see Database Design).

For now: start with a monolith, organize it into components based on functional boundaries, and keep the interfaces between components simple. The rest will become clear as you build.

Real Life Case Studies

Dispatch Management: Progressive Architecture

A B2B SaaS application that evolved from product-market fit validation (100 users) to enterprise scale (10,000+ users). Shows monolith-first strategy with selective microservices extraction only when bottlenecks justified it. Includes complete cost analysis and evolution triggers.

Topics covered: Modular monolith, Docker Compose → Kubernetes → Multi-region, Schema-per-tenant multi-tenancy, Progressive security (Docker secrets → Vault → HSM)

Microfrontend vs. Monolith Decision

See how a finance sector team used a quantitative framework to decide between microfrontends and an extended monolith. Shows the complete decision process with scale analysis, team capability assessment, and financial modeling. Quick read: 7 minutes for Abstract + Conclusion.