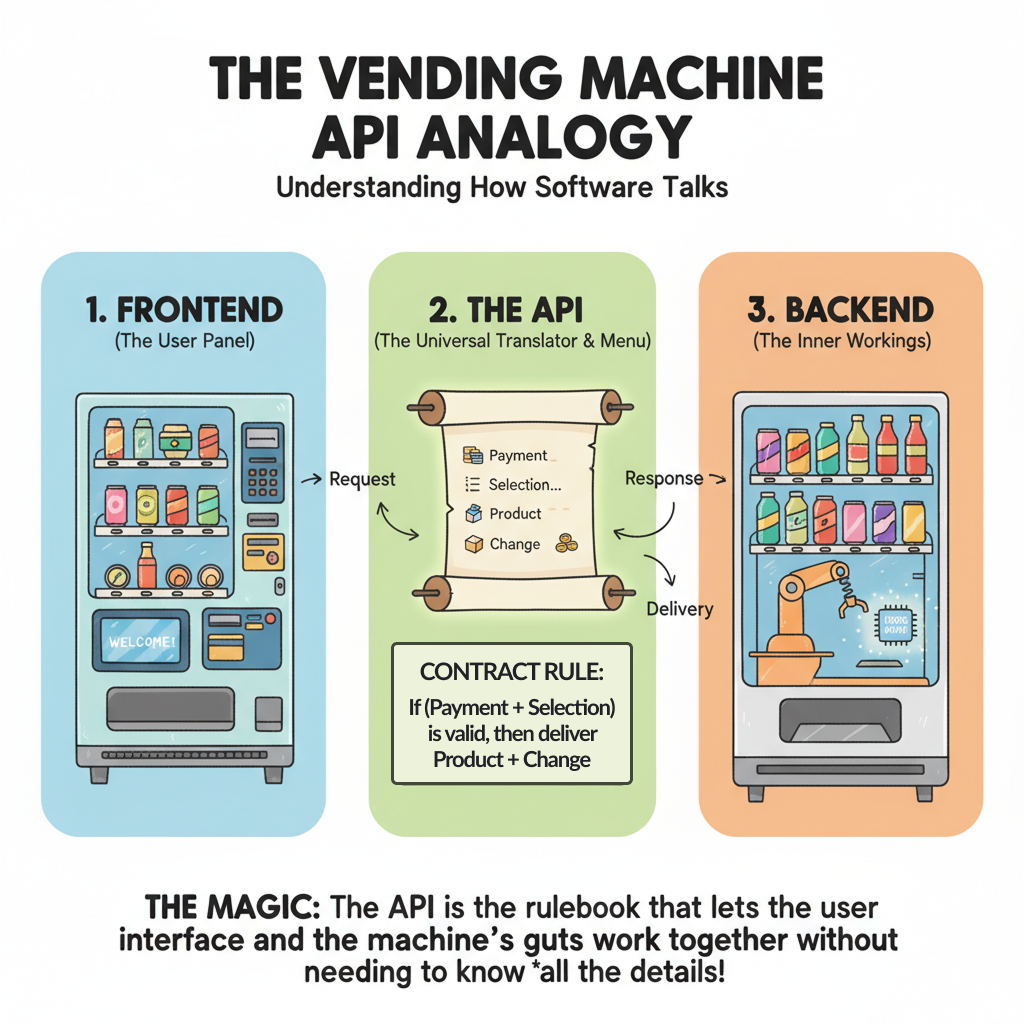

API Design Essentials

Your API is a promise to other developers. It’s how your system talks to the world - whether that’s a mobile app, another service, or a third-party integration. A well-designed API feels obvious to use. A poorly designed one generates support tickets and angry Slack messages.

Image generated with Google Gemini

This guide covers the fundamental decisions that determine whether your API helps or hurts. You don’t need to be a REST purist or memorize the HTTP specification. You need to make consistent, predictable choices that won’t embarrass you six months from now.

What Makes an API Actually Good

Good APIs share three qualities: they’re consistent, they fail clearly, and they don’t surprise you.

Consistency means doing the same thing the same way. If you use user_id in one endpoint, don’t switch to userId in another. If you return arrays in data for list endpoints, don’t suddenly put them in results somewhere else. Your API should feel like one person designed it, even if five people worked on it over two years.

Clear failures mean errors that tell you what went wrong. When something breaks, the error should say what happened and what to do about it. Not “Internal Server Error” - that’s useless. More like “Payment declined: insufficient funds. Verify account balance and retry.”

No surprises means behavior matches expectations. If DELETE /users/123 deletes a user, it shouldn’t also delete all their posts unless that’s documented and obvious. If a field is marked required, it should actually be required. The API should work the way someone would guess it works.

Everything else is refinement.

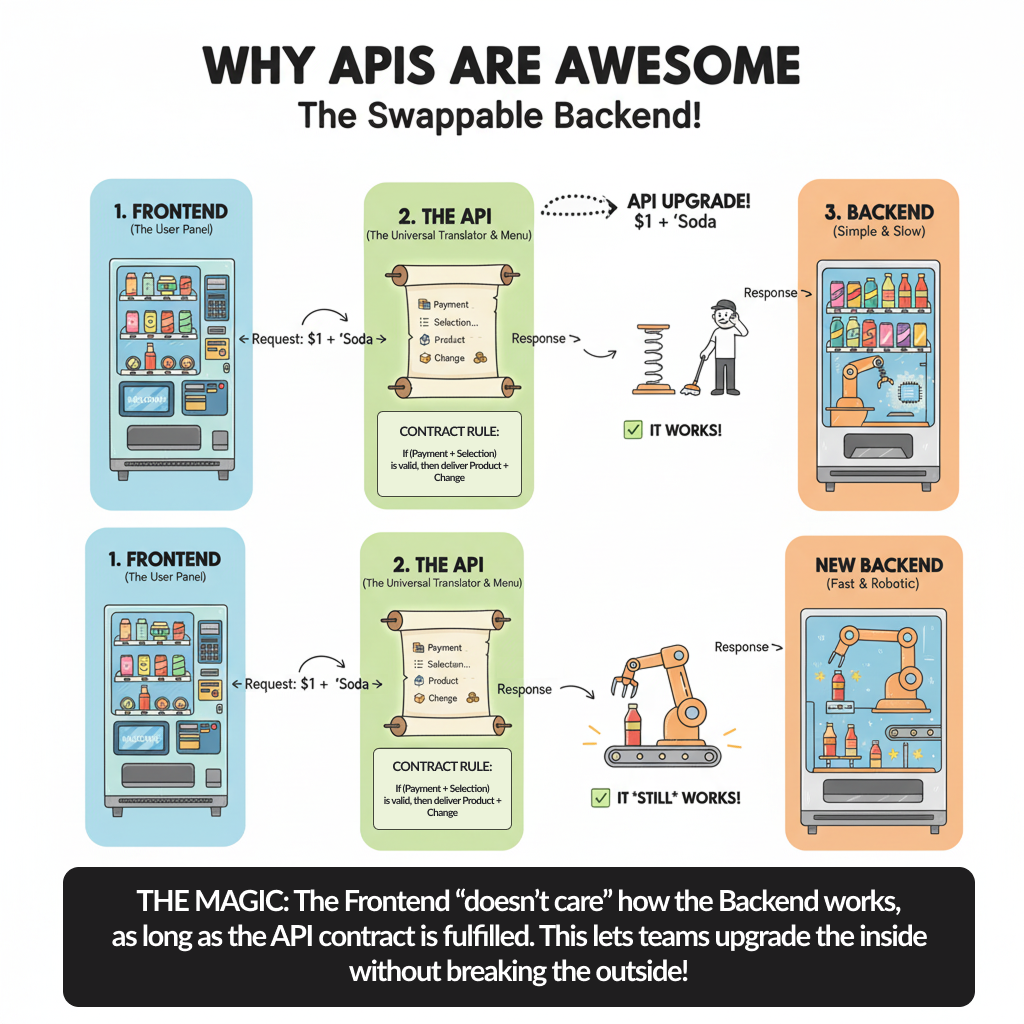

Choosing Your API Style

You have three practical choices: REST-ish, GraphQL, or RPC. Each solves different problems.

Image generated with Google Gemini

REST-ish APIs use HTTP methods and URLs to represent resources. GET /orders/123 fetches an order. POST /orders creates one. PATCH /orders/123 updates it. This is the default choice for public APIs and simple CRUD operations. It’s well-understood, works with standard HTTP tools, and doesn’t require special libraries.

You don’t need perfect REST to benefit from REST-ish design. Real-world APIs violate REST principles constantly. Stripe has /charges/:id/refund as a POST endpoint - technically not RESTful, but completely clear about what it does. Pragmatism wins.

// REST-ish order creation

POST /api/orders

Content-Type: application/json

{

"items": [

{"product_id": "prod_123", "quantity": 2}

],

"shipping_address": {

"street": "123 Main St",

"city": "Portland",

"state": "OR",

"zip": "97201"

}

}

// Response

HTTP/1.1 201 Created

Location: /api/orders/ord_abc123

{

"id": "ord_abc123",

"status": "pending",

"total": 4999,

"currency": "usd",

"created_at": "2025-11-15T10:30:00Z"

}GraphQL lets clients request exactly the data they need. Instead of multiple REST endpoints, you have one endpoint and clients send queries. This solves the “too much data” and “too many requests” problems that plague REST APIs with complex UIs.

GraphQL shines when you have multiple client types (web, mobile, desktop) with different data needs, or when you’re dealing with deeply nested relationships. It’s overkill for simple CRUD apps or public APIs where you control both sides.

# GraphQL query - client specifies exactly what they need

query GetOrder {

order(id: "ord_abc123") {

id

status

total

items {

product {

name

image_url

}

quantity

}

}

}RPC (Remote Procedure Call) treats APIs like function calls. gRPC is the modern version, using Protocol Buffers for fast binary communication. You define methods like CreateOrder() or GetUserProfile() and clients call them like local functions.

Use RPC for internal service-to-service communication where performance matters and you control both ends. It’s not great for public APIs - the tooling requirement is higher and it’s less accessible than REST or GraphQL.

For most projects, start with REST-ish. Switch to GraphQL when you have evidence that REST is causing real problems (too many round trips, over-fetching data). Consider gRPC for internal microservices where you need low latency and type safety.

Resource Design Patterns

Resources are the nouns of your API. In a REST-ish API, everything centers on resources and how you manipulate them.

Use plural nouns for collections. /orders not /order. /users not /user. This reads naturally: GET /orders fetches multiple orders, POST /orders creates a new order. The only exception: singleton resources like /profile or /settings where there’s only ever one per user.

Nest resources to show relationships, but not too deeply. One level of nesting is clear: /orders/123/items shows items belonging to order 123. Two levels starts getting awkward: /customers/456/orders/123/items. Three levels is definitely too much.

When nesting gets deep, flatten it. Instead of /customers/456/orders/123/items/789, use /order-items/789 with query parameters to filter: /order-items?order_id=123&customer_id=456. This is more flexible and doesn’t break when relationships change.

Keep URLs focused on resources, not actions. Use HTTP methods to represent actions:

GET /orders/123- fetch the orderPOST /orders- create an orderPATCH /orders/123- update the orderDELETE /orders/123- cancel/delete the order

Sometimes you need actions that don’t fit CRUD. Slack uses /conversations.create and /conversations.archive. Stripe uses /charges/:id/refund. These are RPC-style endpoints in a REST-ish API. That’s fine - clarity beats purity. Just be consistent about when you break the pattern.

Error Handling That Helps

Errors happen. How you communicate them determines whether developers can fix the problem or just throw their laptop out the window.

Use HTTP status codes correctly. You don’t need to memorize all 50+ status codes. Know these:

200 OK- Request succeeded201 Created- New resource created400 Bad Request- Client sent invalid data401 Unauthorized- Missing or invalid authentication403 Forbidden- Authenticated but not allowed404 Not Found- Resource doesn’t exist429 Too Many Requests- Rate limit exceeded500 Internal Server Error- Something broke on your end503 Service Unavailable- Temporarily down

That covers 95% of situations. If you need to get fancy, 422 Unprocessable Entity is useful for validation errors.

Return error details in the response body. The status code says what category of error. The body says what actually went wrong and how to fix it.

// Helpful error response

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

{

"error": {

"code": "validation_failed",

"message": "Order validation failed",

"details": [

{

"field": "shipping_address.zip",

"issue": "Invalid ZIP code format",

"received": "9999",

"expected": "5 or 9 digit US ZIP code (e.g., 97201 or 97201-1234)"

},

{

"field": "items[0].quantity",

"issue": "Quantity exceeds available stock",

"received": 100,

"available": 12

}

]

}

}This tells the developer exactly what’s wrong and how to fix it. Compare that to:

// Useless error response

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

{

"error": "Invalid request"

}The second version generates a support ticket. The first one gets fixed immediately.

Be consistent with error structure. Every error should have the same shape. If you use error.message sometimes and error_message other times, developers write defensive code to handle both. Pick a structure and stick to it.

Stripe’s error format is solid: type, code, message, param (which field caused the error), and doc_url (link to documentation). GitHub uses message and documentation_url. Both work because they’re consistent.

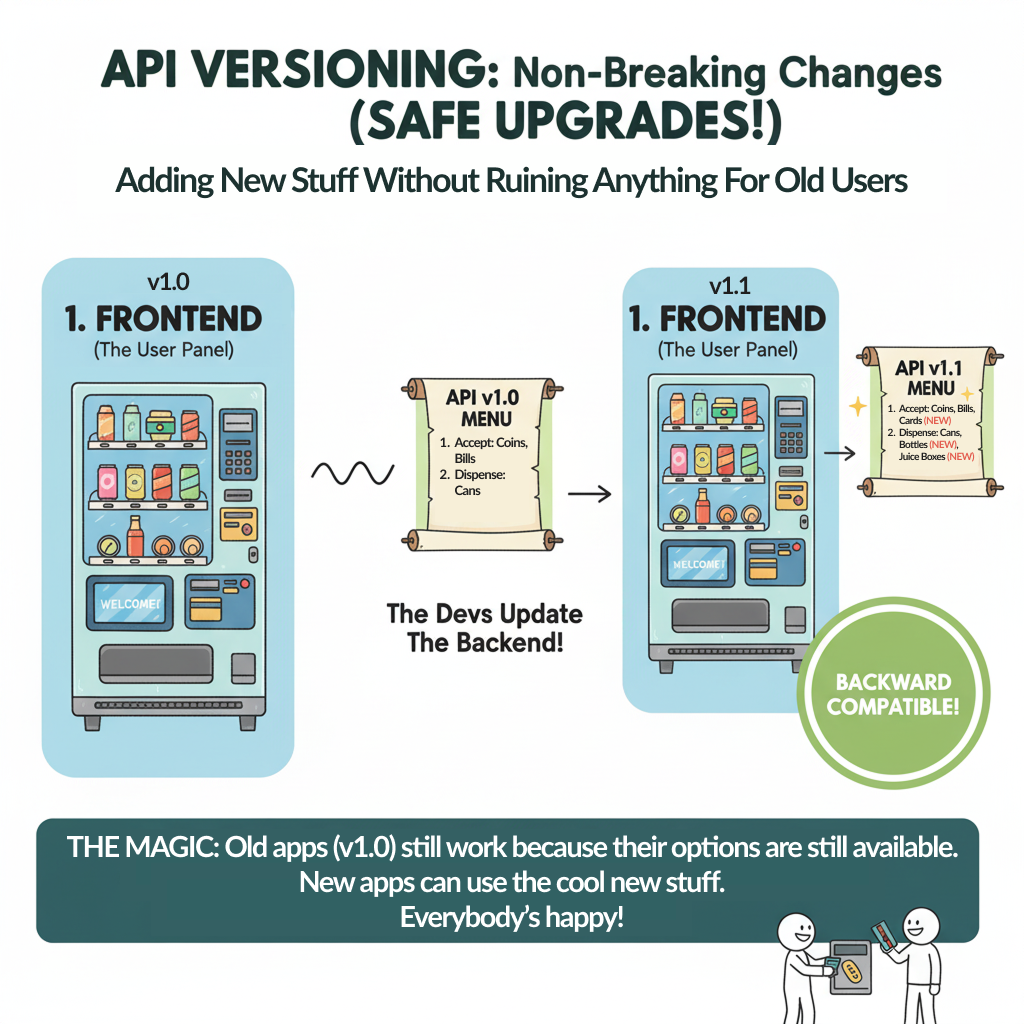

Versioning From Day One

Your API will change. Requirements change, you learn better patterns, third parties request new features. The question isn’t whether to version - it’s how.

Image generated with Google Gemini

Version from the start, even if it feels silly. Having v1 in your first release means v2 isn’t a breaking architectural change. It’s just the next version.

Three versioning strategies work:

URL versioning (/v1/orders, /v2/orders) is the most common. It’s visible, explicit, and works with any HTTP client. You can run multiple versions side-by-side easily. Downside: you end up with version numbers in every URL, which feels redundant.

Header versioning (Accept: application/vnd.myapi.v1+json) keeps URLs clean but makes the API harder to test with basic tools. You can’t just paste a URL in a browser. Every request needs a custom header.

Query parameter versioning (/orders?version=1) is the easiest to implement but feels hacky. It mixes versioning with filtering/pagination parameters and can break caching.

For most APIs, URL versioning wins. It’s clear, it’s explicit, and it works with curl. If you’re building a GraphQL API, versioning is less critical - you evolve the schema by adding fields and deprecating old ones.

When do you bump the version? Breaking changes require a new version. Non-breaking changes don’t.

Breaking changes:

- Removing a field

- Changing field types (string to number)

- Requiring a previously optional field

- Changing URL structure

- Changing error response format

Non-breaking changes:

- Adding new endpoints

- Adding optional fields

- Adding new fields to responses

- Relaxing validation (making required fields optional)

You can add to v1 forever. You only need v2 when you break backward compatibility.

What Good Documentation Looks Like

Your API documentation is not a reference manual. It’s how developers decide whether your API solves their problem and how quickly they can integrate it.

Start with a quick start guide. Show the complete flow from authentication to making a first successful request in under 5 minutes. Use real examples, not placeholders.

// Quick start - complete working example

const response = await fetch('https://api.example.com/v1/orders', {

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Authorization': 'Bearer your_api_key_here',

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

},

body: JSON.stringify({

items: [{product_id: 'prod_123', quantity: 1}]

})

});

const order = await response.json();

console.log('Order created:', order.id);Document common errors with solutions. Don’t just list error codes. Show what causes them and how to fix them.

Provide examples for every endpoint. Request examples, response examples, error examples. Developers copy-paste examples more than they read descriptions. Make the examples worth copying.

Keep authentication obvious. Put auth instructions at the top. Show exactly where the API key or token goes. If you support multiple auth methods (OAuth, API keys, JWT), show examples for each.

Link related endpoints. When documenting POST /orders, link to GET /orders/:id, PATCH /orders/:id, and GET /orders/:id/items. This helps developers discover your API’s capabilities.

Stripe, Twilio, and GitHub have excellent API documentation. They’re worth studying, not to copy, but to understand what makes documentation feel helpful versus exhausting.

Starting Points

Most API decisions can be changed later, but these three are worth getting right from the start:

-

Pick REST-ish unless you have a specific reason not to. It’s the most accessible option and works with every programming language and tool.

-

Version from day one. URL versioning (

/v1/) is the safest default. -

Design your error format before you write endpoint code. Every error should have the same structure, so decide that structure early.

Everything else you can learn as you go. Start simple, stay consistent, and listen when developers complain. They’ll tell you what’s confusing.

Related Topics:

- Architecture Design - How APIs fit into overall system design

- Database Design - Designing the resources your API exposes

- Error Handling & Resilience - Implementation patterns for robust error handling

- Software Design Document - Documenting API decisions and evolution