API Design: Building Interfaces That Scale

You shipped an API. People are using it. Then the problems start: clients are making 50 requests when one would do, rate limits are getting hit by legitimate users, and your database is melting because someone’s polling for updates every second. The API works, but the design decisions you made six months ago are now production incidents at 2am.

This guide covers the patterns that prevent those incidents. Not theoretical best practices, but the specific design choices that determine whether your API is pleasant to use or a source of constant friction.

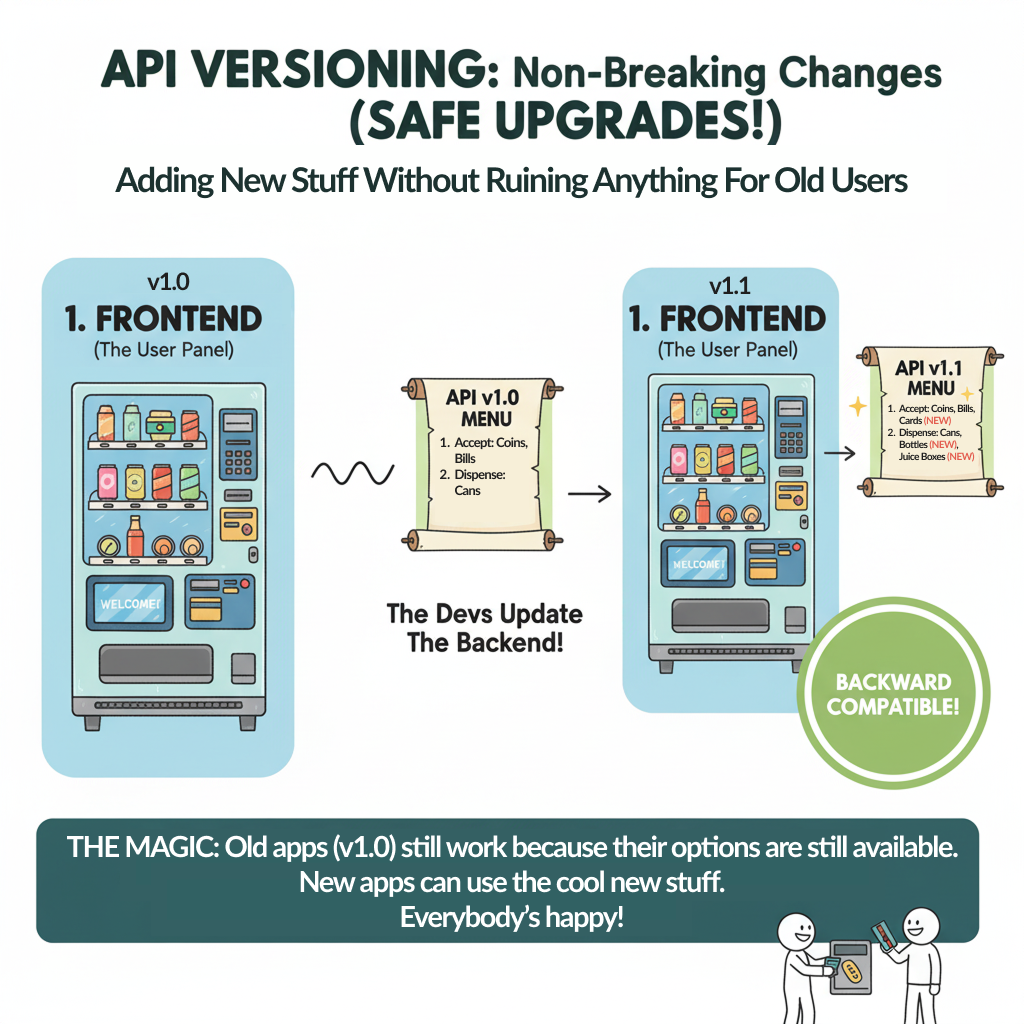

1. Versioning Strategy: Living With Your Past Decisions

You need to change your API. Maybe you named something poorly, maybe the business requirements shifted, maybe you learned something about the domain. Your existing clients are working fine and you don’t want to break them. This is the versioning problem.

Image generated with Google Gemini

I’ve seen teams avoid making necessary improvements because they were paralyzed by versioning. I’ve also seen teams break client integrations because they thought their changes were “backwards compatible” when they weren’t.

What Actually Breaks Compatibility

These changes break existing clients:

- Renaming or removing fields

- Changing field types (string to integer)

- Adding required request parameters

- Removing or renaming endpoints

- Changing error response structures

- Modifying authentication requirements

These are usually safe:

- Adding optional request parameters

- Adding new fields to responses (if clients ignore unknown fields)

- Adding new endpoints

- Making required fields optional

- Relaxing validation rules

The critical question: are your clients resilient to unknown fields? Many JSON parsers will error on unexpected data if you’re using strict typing. That makes adding response fields a breaking change.

URL Versioning: The Pragmatic Default

/v1/users

/v2/usersStripe, Twilio, and GitHub all use URL versioning because it’s explicit and hard to mess up. When you make a request, you’re clearly stating which contract you expect.

Implementation:

// Express router structure

app.use('/v1', v1Routes);

app.use('/v2', v2Routes);

// v1Routes.js

router.get('/users/:id', async (req, res) => {

const user = await db.getUser(req.params.id);

res.json({

id: user.id,

name: user.name,

email: user.email

});

});

// v2Routes.js - added structured name, kept v1 fields

router.get('/users/:id', async (req, res) => {

const user = await db.getUser(req.params.id);

res.json({

id: user.id,

name: user.name, // deprecated but maintained

email: user.email,

full_name: {

first: user.firstName,

last: user.lastName

}

});

});You maintain two versions of the endpoint. Version 1 clients keep working. Version 2 clients get the improved structure.

Sunset Policy:

Don’t maintain old versions forever. Stripe maintains each API version for three years, giving clients ample migration time. Your policy might be:

- Announce new version with migration guide

- Mark old version deprecated after 6 months

- Set sunset date 12-18 months out

- Monitor usage to identify unmigrated clients

- Contact active users of deprecated version

- Remove old version only after usage drops to near-zero

Header Versioning: When URLs Can’t Change

Some teams use header-based versioning:

GET /users/123

Accept: application/vnd.myapi.v2+jsonThis keeps URLs stable but makes versioning less visible. It’s harder to test (you need to set headers), harder to cache (cache keys need to consider version headers), and easier to accidentally call the wrong version.

GitHub uses this for their API. It works for them because they have excellent documentation and sophisticated clients. For most teams, URL versioning is simpler.

The Continuous Versioning Approach

AWS takes a different approach: date-based versioning where you specify the API version as a date:

X-Amz-Target: DynamoDB_20120810.GetItemEvery API change gets a new date. Clients pin to a specific date and are never broken by changes. This works when you have hundreds of services and need absolute stability guarantees.

The downside: you’re essentially maintaining infinite versions. Only feasible if you generate most of your API implementation from schemas.

Version Migration in Practice

// Adapter pattern to reuse logic across versions

class UserService {

async getUser(id) {

return db.query('SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?', [id]);

}

}

// V1 presenter

class UserPresenterV1 {

format(user) {

return {

id: user.id,

name: user.full_name, // Combined

email: user.email

};

}

}

// V2 presenter

class UserPresenterV2 {

format(user) {

return {

id: user.id,

full_name: {

first: user.first_name,

last: user.last_name

},

email: user.email

};

}

}The core logic stays the same. Versions differ only in presentation. This keeps maintenance burden low.

Deprecation Headers:

Help clients migrate by warning them:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Sunset: Sat, 31 Dec 2025 23:59:59 GMT

Deprecation: true

Link: <https://api.example.com/docs/v2-migration>; rel="deprecation"Clients that monitor these headers can proactively migrate before breakage.

2. Pagination and Filtering: Handling Large Result Sets

Your /users endpoint returns 50 users. Six months later it returns 50,000. Now requests are timing out and your mobile app is downloading megabytes of data nobody asked for.

Pagination isn’t optional for any endpoint that returns collections. The question is which pattern fits your use case.

Offset-Based Pagination: The Simple Start

GET /users?limit=20&offset=40How it works:

router.get('/users', async (req, res) => {

const limit = parseInt(req.query.limit) || 20;

const offset = parseInt(req.query.offset) || 0;

const users = await db.query(

'SELECT * FROM users ORDER BY created_at DESC LIMIT ? OFFSET ?',

[limit, offset]

);

const total = await db.query('SELECT COUNT(*) FROM users');

res.json({

data: users,

pagination: {

limit,

offset,

total: total[0].count,

has_more: offset + limit < total[0].count

}

});

});Why it fails at scale:

When you request offset 10,000 with limit 20, the database still has to scan through 10,000 rows to find your starting point. On a large table, this gets slow. Really slow.

Worse: if data is being inserted or deleted while someone’s paginating, they can miss records or see duplicates. User hits page 2, but during that request someone inserted a record at position 15. Now item 21 appears on both page 1 and page 2.

When to use it: Admin interfaces where you need random access to pages (jump to page 47) and total counts. Not for high-traffic APIs or real-time data feeds.

Cursor-Based Pagination: The Scalable Approach

GET /users?limit=20&after=eyJpZCI6MTIzNDU2fQThe cursor is an opaque token that points to a position in the result set. Typically it’s a base64-encoded version of the last record’s ID or timestamp.

Implementation:

router.get('/users', async (req, res) => {

const limit = parseInt(req.query.limit) || 20;

let cursor = null;

if (req.query.after) {

cursor = JSON.parse(Buffer.from(req.query.after, 'base64').toString());

}

let query = 'SELECT * FROM users WHERE deleted_at IS NULL';

const params = [];

if (cursor) {

query += ' AND created_at < ?';

params.push(cursor.timestamp);

}

query += ' ORDER BY created_at DESC LIMIT ?';

params.push(limit + 1); // Fetch one extra to check if there's more

const users = await db.query(query, params);

const hasMore = users.length > limit;

if (hasMore) {

users.pop(); // Remove the extra record

}

let nextCursor = null;

if (hasMore) {

const lastUser = users[users.length - 1];

nextCursor = Buffer.from(JSON.stringify({

timestamp: lastUser.created_at

})).toString('base64');

}

res.json({

data: users,

pagination: {

next_cursor: nextCursor,

has_more: hasMore

}

});

});Why this works:

The database uses an index on created_at. Finding records after a specific timestamp is fast regardless of how deep you are in the result set. No offset scanning.

If data changes between requests, you don’t see duplicates or skips. You’re always moving forward from a known position.

Trade-offs:

- Can’t jump to arbitrary pages (no “page 47”)

- Can’t show total count without a separate query

- Cursor can break if you change sort order or filter criteria

When to use it: Any high-traffic API, mobile apps, infinite scroll, real-time feeds. This is what Twitter, Facebook, and Stripe use for their main APIs.

Keyset Pagination: When Cursors Need to Be Human-Readable

Sometimes you want the benefits of cursor pagination but need the cursor to be a simple value instead of an opaque token:

GET /users?limit=20&after_id=12345router.get('/users', async (req, res) => {

const limit = parseInt(req.query.limit) || 20;

const afterId = req.query.after_id ? parseInt(req.query.after_id) : 0;

const users = await db.query(

`SELECT * FROM users

WHERE id > ?

ORDER BY id ASC

LIMIT ?`,

[afterId, limit + 1]

);

const hasMore = users.length > limit;

if (hasMore) users.pop();

res.json({

data: users,

pagination: {

after_id: hasMore ? users[users.length - 1].id : null,

has_more: hasMore

}

});

});This only works if your ordering column (usually ID) is unique and monotonically increasing. If you sort by created_at, you need a tiebreaker (like ID) because multiple records can have the same timestamp.

Filtering and Sorting

Pagination is half the problem. The other half is letting clients request only what they need.

Basic filtering:

GET /users?role=admin&status=active&limit=20router.get('/users', async (req, res) => {

const { role, status, limit = 20 } = req.query;

let query = 'SELECT * FROM users WHERE 1=1';

const params = [];

if (role) {

query += ' AND role = ?';

params.push(role);

}

if (status) {

query += ' AND status = ?';

params.push(status);

}

query += ' LIMIT ?';

params.push(parseInt(limit));

const users = await db.query(query, params);

res.json({ data: users });

});This works until someone wants to filter by date ranges, partial text matches, or multiple values. Then you need a query language.

Advanced filtering (GraphQL-style):

GET /users?filter={"role":{"in":["admin","moderator"]},"created_at":{"gte":"2024-01-01"}}Now you’re building a query parser. This gets complex fast. Consider using an existing library like query-string or qs for parsing, and Objection.js or Prisma for translating to SQL safely.

The danger: Clients can craft queries that destroy your database. Always whitelist allowed filter fields and add query timeouts.

3. Rate Limiting: Preventing Abuse Without Breaking Legitimate Use

Someone’s polling your API every 100ms. Maybe it’s a bug in their code, maybe it’s intentional. Either way, your database CPU is at 95% and your other customers are seeing timeouts.

Rate limiting isn’t about being mean to your users. It’s about protecting service quality for everyone by preventing any single client from consuming all resources.

Token Bucket Algorithm: The Standard Approach

Think of it like a bucket that holds tokens. Each request costs one token. Tokens refill at a steady rate. When the bucket is empty, requests are rejected until tokens refill.

class TokenBucket {

constructor(capacity, refillRate) {

this.capacity = capacity; // Max tokens

this.tokens = capacity; // Current tokens

this.refillRate = refillRate; // Tokens per second

this.lastRefill = Date.now();

}

tryConsume(tokens = 1) {

this.refill();

if (this.tokens >= tokens) {

this.tokens -= tokens;

return true;

}

return false;

}

refill() {

const now = Date.now();

const timePassed = (now - this.lastRefill) / 1000;

const tokensToAdd = timePassed * this.refillRate;

this.tokens = Math.min(this.capacity, this.tokens + tokensToAdd);

this.lastRefill = now;

}

getRetryAfter() {

this.refill();

const tokensNeeded = 1 - this.tokens;

return Math.ceil(tokensNeeded / this.refillRate);

}

}

// Middleware

const buckets = new Map();

function rateLimiter(req, res, next) {

const key = req.ip; // Or user ID, API key, etc.

if (!buckets.has(key)) {

buckets.set(key, new TokenBucket(100, 10)); // 100 tokens, refill 10/sec

}

const bucket = buckets.get(key);

if (bucket.tryConsume()) {

res.setHeader('X-RateLimit-Limit', bucket.capacity);

res.setHeader('X-RateLimit-Remaining', Math.floor(bucket.tokens));

next();

} else {

res.setHeader('X-RateLimit-Limit', bucket.capacity);

res.setHeader('X-RateLimit-Remaining', 0);

res.setHeader('Retry-After', bucket.getRetryAfter());

res.status(429).json({

error: 'Rate limit exceeded',

retry_after: bucket.getRetryAfter()

});

}

}Why token bucket instead of simple counters:

Token bucket allows bursts. If you haven’t made requests in a while, you have tokens saved up. You can make 100 requests instantly, then you’re throttled to 10/second. This matches real usage patterns better than “exactly 10 per second.”

Distributed rate limiting:

The in-memory approach only works for a single server. In production, you need shared state. Redis is the standard choice:

const Redis = require('ioredis');

const redis = new Redis();

async function checkRateLimit(key, limit, windowSeconds) {

const current = await redis.incr(key);

if (current === 1) {

await redis.expire(key, windowSeconds);

}

if (current > limit) {

const ttl = await redis.ttl(key);

return { allowed: false, retryAfter: ttl };

}

return { allowed: true, remaining: limit - current };

}

// Usage

async function rateLimiter(req, res, next) {

const key = `ratelimit:${req.ip}:${Math.floor(Date.now() / 60000)}`;

const result = await checkRateLimit(key, 100, 60);

if (!result.allowed) {

res.setHeader('Retry-After', result.retryAfter);

return res.status(429).json({ error: 'Rate limit exceeded' });

}

next();

}This is a fixed window counter (100 requests per minute). It’s simpler than token bucket but has an edge case: someone can make 100 requests at 00:59 and another 100 at 01:00, getting 200 requests in two seconds.

For most APIs, this edge case doesn’t matter. If it does, use a sliding window or stick with token bucket in Redis using sorted sets.

Different Limits for Different Endpoints

Not all endpoints are equal. Reading a user profile is cheap. Generating a PDF report from thousands of records is expensive.

const limits = {

'/users': { limit: 1000, window: 3600 }, // 1000/hour

'/reports': { limit: 10, window: 3600 }, // 10/hour

'/exports': { limit: 5, window: 86400 } // 5/day

};

function getRateLimitConfig(path) {

// Match path to config, with defaults

return limits[path] || { limit: 100, window: 60 };

}Headers That Help Clients Adapt

Tell clients about their rate limit status on every response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-RateLimit-Limit: 1000

X-RateLimit-Remaining: 847

X-RateLimit-Reset: 1640000000When they hit the limit:

HTTP/1.1 429 Too Many Requests

X-RateLimit-Limit: 1000

X-RateLimit-Remaining: 0

X-RateLimit-Reset: 1640000000

Retry-After: 42The Retry-After header tells clients exactly how long to wait. Well-behaved clients will respect this and use exponential backoff.

Beyond Simple Rate Limits

Cost-based rate limiting: Different endpoints cost different amounts of tokens. Reading costs 1, writing costs 5, exports cost 50.

Tiered limits: Free tier gets 100/hour, paid tier gets 10,000/hour, enterprise gets custom limits.

Burst limits: Allow 100 requests instantly, then throttle to 10/second sustained.

The complexity is worth it for high-traffic APIs. For most teams starting out, a simple 1000 requests/hour limit is fine.

Tools that help: express-rate-limit for Node.js, django-ratelimit for Python, or use API gateway services like Kong, AWS API Gateway, or Cloudflare that have rate limiting built in.

4. Idempotency: Making Retries Safe

A client submits a payment for $100. The request times out. Did the payment go through? If they retry, will the customer be charged twice?

This is the idempotency problem. Network requests fail. Clients retry. Your API needs to handle the same request multiple times without creating duplicate side effects.

What Needs to Be Idempotent

GET, PUT, and DELETE are naturally idempotent:

- Reading the same resource twice returns the same data

- Updating a resource to the same values multiple times is the same as doing it once

- Deleting something twice has the same effect as deleting it once

POST is not idempotent. Each POST typically creates a new resource. Retry it and you get duplicates.

Idempotency Keys: The Stripe Pattern

The client generates a unique key and sends it with the request:

POST /payments

Idempotency-Key: 7a3f69b8-c5d1-4e9f-a2b4-1c8e7f3d5a9e

{

"amount": 10000,

"currency": "usd",

"customer_id": "cust_123"

}If the same key is sent twice, the API returns the result of the first request without processing again.

Implementation:

const processedRequests = new Map(); // In production: Redis

router.post('/payments', async (req, res) => {

const idempotencyKey = req.headers['idempotency-key'];

if (!idempotencyKey) {

return res.status(400).json({

error: 'Idempotency-Key header required'

});

}

// Check if we've seen this key before

const existing = await redis.get(`idempotency:${idempotencyKey}`);

if (existing) {

const result = JSON.parse(existing);

return res.status(result.status).json(result.body);

}

// Process the payment

try {

const payment = await processPayment(req.body);

// Store the result

const result = {

status: 200,

body: payment

};

await redis.setex(

`idempotency:${idempotencyKey}`,

86400, // 24 hour expiry

JSON.stringify(result)

);

res.json(payment);

} catch (error) {

// Store error results too

const result = {

status: 500,

body: { error: error.message }

};

await redis.setex(

`idempotency:${idempotencyKey}`,

3600, // Shorter expiry for errors

JSON.stringify(result)

);

res.status(500).json(result.body);

}

});Key considerations:

- Keys should expire after 24 hours. Clients shouldn’t reuse keys across days.

- Store both successful and failed responses. If a request failed due to validation, retrying with the same key should return the same validation error, not reprocess.

- The key should be scoped to the user/account. Don’t let one user replay another user’s requests.

Idempotency Without Client Keys

Sometimes clients can’t generate keys (webhooks, third-party integrations). You can make operations idempotent by designing around natural keys:

// Instead of this (not idempotent):

POST /subscriptions

{

"user_id": 123,

"plan": "premium"

}

// Use this (idempotent):

PUT /users/123/subscription

{

"plan": "premium"

}The URL identifies the resource. Sending the same PUT twice has the same effect.

Database-Level Idempotency

Add unique constraints to prevent duplicates:

CREATE TABLE payments (

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

external_id VARCHAR(255) UNIQUE NOT NULL,

amount INTEGER NOT NULL,

customer_id INTEGER NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

);async function createPayment(externalId, amount, customerId) {

try {

const payment = await db.query(

`INSERT INTO payments (external_id, amount, customer_id)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3)

RETURNING *`,

[externalId, amount, customerId]

);

return payment;

} catch (error) {

if (error.code === '23505') { // Unique violation

// Payment already exists, return existing record

return await db.query(

'SELECT * FROM payments WHERE external_id = $1',

[externalId]

);

}

throw error;

}

}The database enforces uniqueness. Attempting to insert the same external ID twice returns the existing record instead of creating a duplicate.

This is simpler than idempotency keys but less flexible. It only works if you have a natural unique identifier.

5. Field Selection and Expansion: Letting Clients Request What They Need

Your /users/123 endpoint returns this:

{

"id": 123,

"name": "Alice",

"email": "alice@example.com",

"created_at": "2024-01-15",

"updated_at": "2024-11-15",

"avatar_url": "https://...",

"bio": "...",

"settings": { /* 50 fields */ },

"preferences": { /* 30 fields */ },

"notifications": [ /* array of 200 items */ ]

}The mobile app only needs name and avatar. It’s downloading 50KB when 200 bytes would do. Your database is joining 4 tables when 1 would be enough.

Sparse Fieldsets: Request Only What You Need

GET /users/123?fields=id,name,avatar_url{

"id": 123,

"name": "Alice",

"avatar_url": "https://..."

}Implementation:

router.get('/users/:id', async (req, res) => {

const userId = req.params.id;

const requestedFields = req.query.fields?.split(',') || null;

const user = await db.getUser(userId);

if (requestedFields) {

const filtered = {};

requestedFields.forEach(field => {

if (user.hasOwnProperty(field)) {

filtered[field] = user[field];

}

});

return res.json(filtered);

}

res.json(user);

});This is simple but wastes database queries. You still fetch everything then filter in memory.

Better approach with projection:

router.get('/users/:id', async (req, res) => {

const userId = req.params.id;

const requestedFields = req.query.fields?.split(',') || ['*'];

// Validate against whitelist

const allowedFields = ['id', 'name', 'email', 'avatar_url', 'bio'];

const fields = requestedFields.filter(f => allowedFields.includes(f));

if (fields.length === 0) {

return res.status(400).json({ error: 'No valid fields requested' });

}

const user = await db.query(

`SELECT ${fields.join(', ')} FROM users WHERE id = ?`,

[userId]

);

res.json(user);

});Now you’re only fetching what the client needs. Much better for performance.

Security note: Always whitelist allowed fields. Don’t let clients request password_hash or other internal fields.

Resource Expansion: Avoiding N+1 Queries

You’re building a blog feed. Each post has an author. The naive approach:

GET /posts?limit=10Returns:

{

"data": [

{

"id": 1,

"title": "Post 1",

"author_id": 42,

"content": "..."

},

// ... 9 more posts

]

}Now the client makes 10 more requests to fetch each author. That’s 11 requests total for one screen. This is the N+1 query problem.

Solution: Allow expanding relations

GET /posts?limit=10&expand=author{

"data": [

{

"id": 1,

"title": "Post 1",

"author": {

"id": 42,

"name": "Bob",

"avatar_url": "https://..."

},

"content": "..."

}

]

}Implementation:

router.get('/posts', async (req, res) => {

const expand = req.query.expand?.split(',') || [];

const posts = await db.query('SELECT * FROM posts LIMIT 10');

if (expand.includes('author')) {

const authorIds = posts.map(p => p.author_id);

const authors = await db.query(

'SELECT * FROM users WHERE id IN (?)',

[authorIds]

);

const authorMap = new Map(authors.map(a => [a.id, a]));

posts.forEach(post => {

post.author = authorMap.get(post.author_id);

delete post.author_id; // Replace ID with full object

});

}

res.json({ data: posts });

});Two database queries instead of 11 API requests. The client gets everything in one round trip.

Nested expansion:

GET /posts?expand=author,comments,comments.authorThis can get complex quickly. Consider limits:

- Maximum expansion depth (2-3 levels)

- Maximum number of expandable relations per request

- Some relations might be too large to expand (don’t allow expanding all 10,000 followers)

Stripe’s API handles this well. Check their expansion documentation for patterns.

GraphQL as an Alternative

If you find yourself building extensive field selection and expansion, you’re reinventing GraphQL. It’s designed for exactly this use case:

query {

posts(limit: 10) {

id

title

author {

name

avatar_url

}

comments {

text

author {

name

}

}

}

}GraphQL has its own complexity (N+1 query problem, query depth limits, caching challenges), but if your API needs are sophisticated, it might be worth the investment.

For most REST APIs, sparse fieldsets plus limited expansion is sufficient.

6. Webhooks: Pushing Updates Instead of Polling

Your customer wants to know when payments complete. The bad solution: poll your API every second. The good solution: webhooks.

A webhook is a reverse API call. Instead of the client requesting data, your API sends data to the client when events happen.

Basic Webhook Implementation

1. Client registers a webhook URL:

POST /webhooks

{

"url": "https://customer.com/webhooks/payments",

"events": ["payment.completed", "payment.failed"]

}2. Your system calls that URL when events occur:

async function notifyWebhooks(eventType, data) {

const webhooks = await db.query(

'SELECT * FROM webhooks WHERE events @> $1',

[[eventType]]

);

for (const webhook of webhooks) {

try {

await axios.post(webhook.url, {

id: generateEventId(),

type: eventType,

created_at: new Date().toISOString(),

data: data

}, {

timeout: 5000,

headers: {

'X-Webhook-Signature': generateSignature(data, webhook.secret)

}

});

} catch (error) {

// Log failure, queue for retry

await queueWebhookRetry(webhook.id, eventType, data);

}

}

}

// When a payment completes:

await notifyWebhooks('payment.completed', {

payment_id: payment.id,

amount: payment.amount,

customer_id: payment.customer_id

});Challenges and Solutions

Problem 1: Client endpoint is down

Your webhook fails. Now what?

Use exponential backoff retry:

async function retryWebhook(webhook, attempt = 1) {

const delays = [60, 300, 900, 3600, 7200]; // 1min, 5min, 15min, 1hr, 2hr

const delay = delays[Math.min(attempt - 1, delays.length - 1)] * 1000;

await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, delay));

try {

await sendWebhook(webhook);

} catch (error) {

if (attempt < 5) {

await retryWebhook(webhook, attempt + 1);

} else {

// Give up, mark webhook as failed

await markWebhookFailed(webhook.id);

}

}

}Problem 2: Security - how does client know it’s really you?

Sign webhook payloads with HMAC:

const crypto = require('crypto');

function generateSignature(payload, secret) {

return crypto

.createHmac('sha256', secret)

.update(JSON.stringify(payload))

.digest('hex');

}

// Client verifies:

function verifySignature(payload, signature, secret) {

const expected = generateSignature(payload, secret);

return crypto.timingSafeEqual(

Buffer.from(signature),

Buffer.from(expected)

);

}The secret is shared when the webhook is registered. Only someone with the secret can generate valid signatures.

Problem 3: Duplicate deliveries

Network issues can cause webhooks to be delivered multiple times. Include an event ID and document that clients should handle duplicates:

{

"id": "evt_1a2b3c4d",

"type": "payment.completed",

"created_at": "2024-11-15T10:30:00Z",

"data": { ... }

}Clients should track processed event IDs and ignore duplicates.

Problem 4: Ordering

Events can arrive out of order. Include timestamps and sequence numbers. Document that clients shouldn’t assume ordering.

Webhook Management Features

Give clients tools to debug:

1. Test endpoint:

POST /webhooks/test

{

"webhook_id": "wh_123"

}Sends a test event immediately so they can verify their endpoint works.

2. Event log:

GET /webhooks/events?webhook_id=wh_123Returns history of all events sent to that webhook, including retry attempts and final status.

3. Replay:

POST /webhooks/events/evt_abc/replayResend a specific event. Useful when their endpoint was misconfigured and they missed events.

When to Use Webhooks vs. Polling

Use webhooks when:

- Events are infrequent (less than once per minute)

- Near-real-time updates matter

- You want to reduce server load from polling

Use polling when:

- Client can’t receive inbound connections (mobile apps, browsers)

- Events are frequent and batching makes sense

- Client needs to control request timing

Use WebSockets when:

- You need true real-time bidirectional communication

- Events are very frequent

- You’re building chat, collaboration, or live updates

Many services support both webhooks and polling. Stripe does this well - webhooks for server-to-server, polling for dashboard updates.

7. Error Handling and Status Codes: Helping Clients Recover

Your API returns:

HTTP/1.1 500 Internal Server Error

{

"error": "Something went wrong"

}The client has no idea what happened or how to fix it. This is useless.

Good error responses tell clients:

- What went wrong

- Why it went wrong

- How to fix it

- Whether retrying will help

HTTP Status Codes That Matter

2xx Success:

200 OK- Request succeeded, here’s the data201 Created- Resource created, here’s the new resource202 Accepted- Request accepted for async processing204 No Content- Success but no data to return (useful for DELETE)

4xx Client Errors (don’t retry):

400 Bad Request- Malformed request, invalid JSON, missing required fields401 Unauthorized- No valid authentication credentials403 Forbidden- Authenticated but not authorized for this resource404 Not Found- Resource doesn’t exist409 Conflict- Request conflicts with current state (duplicate username, optimistic locking failure)422 Unprocessable Entity- Valid syntax but semantic errors (validation failures)429 Too Many Requests- Rate limit exceeded

5xx Server Errors (retrying might help):

500 Internal Server Error- Unexpected server problem502 Bad Gateway- Upstream service failed503 Service Unavailable- Temporarily down, try again later504 Gateway Timeout- Upstream service timed out

The distinction between 4xx and 5xx tells clients whether retrying makes sense. 4xx means the request is wrong - retrying the same request will fail again. 5xx means something’s wrong on the server - retrying might succeed.

Error Response Structure

{

"error": {

"type": "validation_error",

"message": "Request validation failed",

"details": [

{

"field": "email",

"code": "invalid_format",

"message": "Email address is not valid"

},

{

"field": "age",

"code": "out_of_range",

"message": "Age must be between 18 and 120"

}

],

"documentation_url": "https://docs.api.com/errors/validation_error"

}

}Key elements:

type: Machine-readable error categorymessage: Human-readable summarydetails: Array of specific issues (especially for validation)documentation_url: Link to docs explaining this error

Validation Errors

When a request fails validation, tell the client exactly what’s wrong:

router.post('/users', async (req, res) => {

const errors = [];

if (!req.body.email || !isValidEmail(req.body.email)) {

errors.push({

field: 'email',

code: 'invalid_format',

message: 'Valid email address is required'

});

}

if (!req.body.password || req.body.password.length < 8) {

errors.push({

field: 'password',

code: 'too_short',

message: 'Password must be at least 8 characters'

});

}

if (errors.length > 0) {

return res.status(422).json({

error: {

type: 'validation_error',

message: 'Request validation failed',

details: errors

}

});

}

// Process valid request

const user = await createUser(req.body);

res.status(201).json(user);

});This lets clients show inline error messages next to form fields instead of generic “something went wrong.”

Error Codes for Common Scenarios

const ErrorTypes = {

VALIDATION_ERROR: 'validation_error',

AUTHENTICATION_REQUIRED: 'authentication_required',

INSUFFICIENT_PERMISSIONS: 'insufficient_permissions',

RESOURCE_NOT_FOUND: 'resource_not_found',

RATE_LIMIT_EXCEEDED: 'rate_limit_exceeded',

IDEMPOTENCY_ERROR: 'idempotency_error',

EXTERNAL_SERVICE_ERROR: 'external_service_error',

DATABASE_ERROR: 'database_error'

};

function errorResponse(type, message, details = null, statusCode = 500) {

return {

error: {

type,

message,

details,

timestamp: new Date().toISOString(),

documentation_url: `https://docs.api.com/errors/${type}`

}

};

}

// Usage:

res.status(429).json(

errorResponse(

ErrorTypes.RATE_LIMIT_EXCEEDED,

'You have exceeded your rate limit',

{ limit: 100, window: '1 hour', retry_after: 1847 },

429

)

);What Not to Expose

Don’t leak internal details in errors:

Bad:

{

"error": "ERROR 1064 (42000): You have an error in your SQL syntax near 'WHERE user_id ='"

}This tells attackers about your database structure and SQL injection vulnerabilities.

Good:

{

"error": {

"type": "database_error",

"message": "Unable to process request due to a temporary database issue",

"request_id": "req_a1b2c3d4"

}

}Log the details server-side. Return a request ID so support can look up the specific error when the client reports it.

Structured Logging for Debugging

const logger = require('pino')();

router.post('/payments', async (req, res) => {

const requestId = generateRequestId();

try {

logger.info({

request_id: requestId,

method: 'POST',

path: '/payments',

user_id: req.user.id,

amount: req.body.amount

}, 'Processing payment');

const payment = await processPayment(req.body);

logger.info({

request_id: requestId,

payment_id: payment.id,

status: 'completed'

}, 'Payment processed');

res.json(payment);

} catch (error) {

logger.error({

request_id: requestId,

error: error.message,

stack: error.stack,

user_id: req.user.id

}, 'Payment processing failed');

res.status(500).json({

error: {

type: 'payment_error',

message: 'Unable to process payment',

request_id: requestId

}

});

}

});When a client reports “my payment failed,” support can search logs by request_id to see exactly what happened.

8. Documentation and Developer Experience

Your API can be perfectly designed, but if developers can’t figure out how to use it, it might as well not exist.

I’ve seen APIs with great technical design that nobody uses because the documentation was cryptic. I’ve also seen mediocre APIs with excellent docs that became widely adopted.

What Makes Good API Documentation

1. Getting started in under 5 minutes:

## Quick Start

1. Get your API key from the [dashboard](https://app.example.com/api-keys)

2. Make your first request:

```bash

curl https://api.example.com/users/me \

-H "Authorization: Bearer YOUR_API_KEY"That’s it. You should see your user profile.

Developers want to see a working example immediately, then learn the details.

**2. Complete request/response examples:**

Don't just show the request:

```markdown

### Create a payment

**Request:**

POST /payments

Authorization: Bearer sk_test_123

Content-Type: application/json

{

"amount": 10000,

"currency": "usd",

"customer": "cust_abc123"

}

**Response:**

HTTP/1.1 201 Created

{

"id": "pay_xyz789",

"amount": 10000,

"currency": "usd",

"status": "succeeded",

"created_at": "2024-11-15T10:30:00Z"

}

**Possible errors:**

- 400: Invalid amount (must be positive integer)

- 404: Customer not found

- 429: Rate limit exceededShow the request, the successful response, and common errors.

3. Code examples in multiple languages:

### Example

**cURL:**

```bash

curl -X POST https://api.example.com/users \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"name":"Alice","email":"alice@example.com"}'JavaScript:

const response = await fetch('https://api.example.com/users', {

method: 'POST',

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' },

body: JSON.stringify({ name: 'Alice', email: 'alice@example.com' })

});

const user = await response.json();Python:

import requests

response = requests.post('https://api.example.com/users',

json={'name': 'Alice', 'email': 'alice@example.com'})

user = response.json()

Developers copy-paste. Make it easy.

### Interactive Documentation with OpenAPI

OpenAPI (formerly Swagger) lets you define your API in YAML and generate interactive docs:

```yaml

openapi: 3.0.0

info:

title: Example API

version: 1.0.0

paths:

/users:

post:

summary: Create a new user

requestBody:

required: true

content:

application/json:

schema:

type: object

required:

- name

- email

properties:

name:

type: string

example: Alice

email:

type: string

format: email

example: alice@example.com

responses:

201:

description: User created

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/User'

422:

description: Validation error

components:

schemas:

User:

type: object

properties:

id:

type: integer

name:

type: string

email:

type: stringTools like Swagger UI and Redoc turn this into interactive documentation where developers can try requests directly in the browser.

Even better, you can generate SDKs from the spec using OpenAPI Generator.

SDK Design

Hand-written SDKs provide better developer experience than auto-generated ones, but they’re much more work to maintain.

Good SDK:

const client = new APIClient('your_api_key');

const user = await client.users.create({

name: 'Alice',

email: 'alice@example.com'

});

const payments = await client.payments.list({

customer: user.id,

limit: 10

});Auto-generated SDK:

const api = new DefaultApi(config);

const user = await api.usersPost({

createUserRequest: {

name: 'Alice',

email: 'alice@example.com'

}

});The hand-written version feels natural. The generated version exposes API details (HTTP methods in function names).

If you can only maintain one SDK, pick JavaScript or Python (depending on your audience). Let the community build the rest, or use generated SDKs for other languages.

Changelog and Migration Guides

When you release a new API version, provide a migration guide:

## Migrating from v1 to v2

### Breaking changes

**User object structure**

v1 returned:

```json

{ "id": 123, "name": "Alice Smith" }v2 returns:

{

"id": 123,

"full_name": {

"first": "Alice",

"last": "Smith"

}

}Action required: Update your code to use full_name.first and full_name.last instead of name.

New features

- Pagination now supports cursor-based navigation

- Rate limits increased to 1000 requests/hour

- Webhooks now include retry information

Make it scannable. Developers will skim for what they need to change.

### Testing Tools

Provide a sandbox environment:

- Test API keys that don't charge real money

- Fake data that behaves like production

- Tools to trigger edge cases (simulate failures, rate limits, timeouts)

Stripe's test mode is the gold standard. You can simulate any scenario without affecting real data.

### Developer Support

Even great docs don't cover everything. Make it easy to get help:

- **API status page**: Is the problem me or you?

- **Community forum**: Common questions get answered by the community

- **Support tickets**: Direct help for paying customers

- **GitHub issues**: For SDK bugs and feature requests

The best APIs have multiple layers of support so developers can self-serve for simple questions and get expert help for complex issues.

---

## Putting It Together: API Design Checklist

When designing an endpoint, work through this list:

**Basic structure:**

- [ ] Endpoint follows RESTful conventions

- [ ] Uses appropriate HTTP method (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE)

- [ ] Returns correct status codes

- [ ] Response includes all necessary data

**Scalability:**

- [ ] Collections are paginated (cursor-based if high-traffic)

- [ ] Supports field selection to reduce payload size

- [ ] Allows expanding relations to avoid N+1 queries

- [ ] Rate limited appropriately for endpoint cost

**Reliability:**

- [ ] POST endpoints support idempotency keys

- [ ] Errors include actionable information

- [ ] Retries are safe (GET, PUT, DELETE) or explicitly handled (POST)

- [ ] Timeout values are documented

**Security:**

- [ ] Authentication required

- [ ] Authorization checked

- [ ] Input validated

- [ ] Errors don't leak internal details

- [ ] Sensitive data not in URLs

**Developer experience:**

- [ ] Documented with request/response examples

- [ ] Code samples in at least one language

- [ ] Error responses explain how to fix

- [ ] Versioned with clear migration path

**Observability:**

- [ ] Requests logged with unique IDs

- [ ] Errors logged with context

- [ ] Rate limit headers included

- [ ] Deprecation warnings if applicable

You don't need to check every box for every endpoint. But if you're skipping something, do it consciously with a good reason.

## Tools and Libraries

**Node.js:**

- [Express](https://expressjs.com/) or [Fastify](https://www.fastify.io/) for routing

- [express-rate-limit](https://github.com/express-rate-limit/express-rate-limit) for rate limiting

- [joi](https://joi.dev/) or [zod](https://zod.dev/) for validation

- [pino](https://getpino.io/) for structured logging

**Python:**

- [FastAPI](https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/) (auto-generates OpenAPI docs)

- [Django REST Framework](https://www.django-rest-framework.org/)

- [flask-limiter](https://flask-limiter.readthedocs.io/) for rate limiting

- [marshmallow](https://marshmallow.readthedocs.io/) for validation

**API Gateway:**

- [Kong](https://konghq.com/) - Open source, handles auth, rate limiting, logging

- [AWS API Gateway](https://aws.amazon.com/api-gateway/) - Managed service

- [Cloudflare](https://www.cloudflare.com/application-services/products/api-gateway/) - CDN + API features

**Documentation:**

- [Swagger UI](https://swagger.io/tools/swagger-ui/) - Interactive docs from OpenAPI

- [Redoc](https://redocly.com/redoc) - Beautiful OpenAPI docs

- [Postman](https://www.postman.com/) - Testing and auto-generated docs

- [ReadMe](https://readme.com/) - Hosted documentation platform

**Monitoring:**

- [Datadog](https://www.datadoghq.com/) - Full observability platform

- [Sentry](https://sentry.io/) - Error tracking

- [LogDNA](https://www.logdna.com/) / [Logtail](https://betterstack.com/logtail) - Log aggregation

## What We Covered

This guide walked through the decisions that determine whether your API is easy to work with or a constant source of friction:

1. **Versioning** lets you improve your API without breaking existing clients

2. **Pagination** keeps response sizes manageable as data grows

3. **Rate limiting** protects your service from overload

4. **Idempotency** makes retries safe

5. **Field selection and expansion** reduce over-fetching

6. **Webhooks** eliminate wasteful polling

7. **Error handling** helps clients recover from failures

8. **Documentation** determines whether developers can actually use your API

The patterns here aren't theoretical. They're battle-tested approaches from high-traffic APIs like Stripe, GitHub, and Twilio. You don't need to implement everything on day one, but knowing these patterns lets you make informed trade-offs.

## Related Topics

- **[Database Design](../../database-design/mid-depth/)** - Database design affects API performance

- **[Architecture Design](../../architecture-design/mid-depth/)** - How APIs fit into overall system architecture

- **[Performance & Scalability Design](../../performance-scalability-design/mid-depth/)** - Query optimization and caching strategies

- **[Error Handling & Resilience](../../error-handling-resilience/mid-depth/)** - Implementing robust error handling in your application

- **[Monitoring & Logging](../../../06-operations/monitoring-logging/mid-depth/)** - Tracking API usage and debugging issues